eMedicine Specialties > Gastroenterology > Esophagus

Updated: Apr 28, 2009

Background

Gastroesophageal reflux is a normal physiologic phenomenon experienced intermittently by most people, particularly after a meal. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when the amount of gastric juice that refluxes into the esophagus exceeds the normal limit, causing symptoms with or without associated esophageal mucosal injury (ie, esophagitis).

For excellent patient education resources, visit eMedicine's Heartburn/GERD/Reflux Center and Esophagus, Stomach, and Intestine Center. Also, see eMedicine's patient education articles Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), Heartburn, and Heartburn/GERD Medications.

Pathophysiology

The physiologic and anatomic factors that prevent the reflux of gastric juice from the stomach into the esophagus include the following:

- The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) must have a normal length and pressure and a normal number of episodes of transient relaxation (relaxation in the absence of swallowing).

- The gastroesophageal junction must be located in the abdomen so that the diaphragmatic crura can assist the action of the LES, thus functioning as an extrinsic sphincter. The presence of a hiatal hernia disrupts this synergistic action and can promote reflux (see Image 3 or below).

- Esophageal clearance must be able to neutralize the acid refluxed through the LES. (Mechanical clearance is achieved with esophageal peristalsis. Chemical clearance is achieved with saliva.)

- The stomach must empty properly.

Abnormal gastroesophageal reflux is caused by the abnormalities of one or more of the following protective mechanisms:

- A functional (frequent transient LES relaxation) or mechanical (hypotensive LES) problem of the LES is the most common cause of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Certain foods (eg, coffee, alcohol), medications (eg, calcium channel blockers, nitrates, beta-blockers), or hormones (eg, progesterone) can decrease the pressure of the LES.

- Obesity is a contributing factor in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), probably because of the increased intra-abdominal pressure.

From a therapeutic point of view, informing patients that gastric refluxate is made up not only of acid but also of duodenal contents (eg, bile, pancreatic secretions) is important.

Frequency

United States

Heartburn is a common problem in the United States and in the Western world. Approximately 7% of the population experience symptoms of heartburn daily. An abnormal esophageal exposure to gastric juice is probably present in 20-40% of this population, meaning 20-40% of the people who experience heartburn do indeed have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In the remaining population, heartburn is probably due to other causes. Because many individuals control symptoms with over-the-counter (OTC) medications and without consulting a medical professional, the condition is likely underreported.

Mortality/Morbidity

- In addition to the typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) (eg, heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia), abnormal reflux can cause atypical symptoms, such as coughing, chest pain, and wheezing. Additional atypical symptoms from abnormal reflux include damage to the lungs (eg, pneumonia, asthma, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis), vocal cords (eg, laryngitis, cancer), ear (eg, otitis media), and teeth (eg, enamel decay).

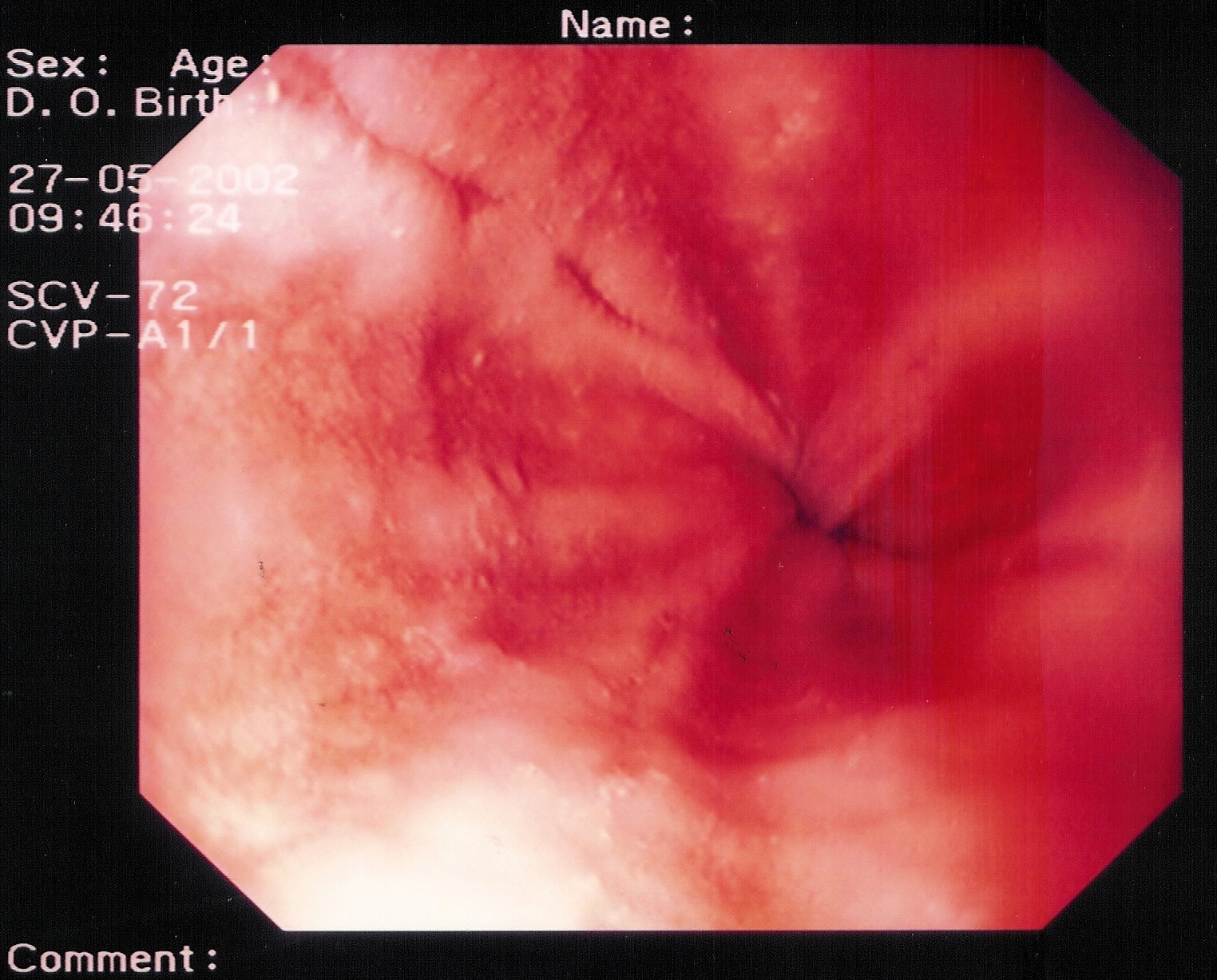

- Approximately 50% of patients with gastric reflux develop esophagitis (see Image 6 or below).

Peptic esophagitis. A rapid urease test (RUT) is performed on the esophageal biopsy sample. The result is positive for esophagitis.

{{mediacaption:1674250_0}}Esophagitis is classified into the following 4 grades based on its severity:- Grade I – Erythema

- Grade II – Linear nonconfluent erosions

- Grade III – Circular confluent erosions

- Grade IV – Stricture or Barrett esophagus. Barrett esophagus is thought to be caused by the chronic reflux of gastric juice into the esophagus. Barrett esophagus occurs when the squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by the intestinal columnar epithelium (see Image 1 or below).

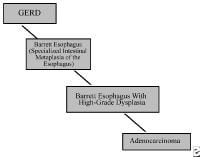

{{mediacaption:176678_1}}Barrett esophagus is present in 8-15% of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and may progress to adenocarcinoma (see Images 2 and 7 or below).

{{mediacaption:1674255_3}}See Esophageal Cancer.

Race

- White males are at a greater risk for Barrett esophagus and adenocarcinoma than other populations.

Sex

- No sexual predilection exists. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is as common in men as in women.

- The male-to-female incidence ratio for esophagitis is 2:1-3:1. The male-to-female incidence ratio for Barrett esophagus is 10:1.

Age

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs in all age groups.

- The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) increases in people older than 40 years.

Clinical

History

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can cause typical (esophageal) symptoms or atypical (extraesophageal) symptoms. However, a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) based on the presence of typical symptoms is correct in only 70% of patients.

- Typical (esophageal) symptoms include the following:

- Heartburn is the most common typical symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Heartburn is felt as a retrosternal sensation of burning or discomfort that usually occurs after eating or when lying down or bending over.

- Regurgitation is an effortless return of gastric and/or esophageal contents into the pharynx. Regurgitation can induce respiratory complications if gastric contents spill into the tracheobronchial tree.

- Dysphagia occurs in approximately one third of patients because of a mechanical stricture or a functional problem (eg, nonobstructive dysphagia secondary to abnormal esophageal peristalsis). Patients with dysphagia experience a sensation that food is stuck, particularly in the retrosternal area.

- Atypical (extraesophageal) symptoms include the following:

- Coughing and/or wheezing are respiratory symptoms resulting from the aspiration of gastric contents into the tracheobronchial tree or from the vagal reflex arc producing bronchoconstriction. Approximately 50% of patients who have GERD-induced asthma do not experience heartburn.

- Hoarseness results from irritation of the vocal cords by gastric refluxate and is often experienced by patients in the morning.

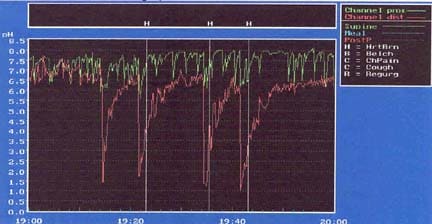

- Reflux is the most common cause of noncardiac chest pain, accounting for approximately 50% of cases. Patients can present to the emergency department with pain resembling a myocardial infarction. Reflux should be ruled out (using esophageal manometry and 24-h pH testing if necessary) once a cardiac cause for the chest pain has been excluded. Alternatively, a therapeutic trial of a high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) can be tried.

Physical

The physical examination is noncontributory.

References

[Best Evidence] Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med. Aug 2 2005;143(3):199-211. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Herbella FA, Sweet MP, Tedesco P, Nipomnick I, Patti MG. Gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity. Pathophysiology and implications for treatment. J Gastrointest Surg. Mar 2007;11(3):286-90. [Medline].

Merrouche M, Sabate JM, Jouet P, et al. Gastro-esophageal reflux and esophageal motility disorders in morbidly obese patients before and after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. Jul 2007;17(7):894-900. [Medline].

Murray L, Johnston B, Lane A, et al. Relationship between body mass and gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: The Bristol Helicobacter Project. Int J Epidemiol. Aug 2003;32(4):645-50. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Pandolfino JE, El-Serag HB, Zhang Q, et al. Obesity: a challenge to esophagogastric junction integrity. Gastroenterology. Mar 2006;130(3):639-49. [Medline].

El-Serag HB, Graham DY, Satia JA, Rabeneck L. Obesity is an independent risk factor for GERD symptoms and erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. Jun 2005;100(6):1243-50. [Medline].

Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. Dec 27 2006;296(24):2947-53. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparative Effectiveness of Management Strategies for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease - Executive Summary. AHRQ pub. no. 06-EHC003-1. December 2005. Available at http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/healthInfo.cfm?infotype=rr&ProcessID=1&DocID=42. Accessed April 21, 2009.

Lundell L, Miettinen P, Myrvold HE, et al. Continued (5-year) followup of a randomized clinical study comparing antireflux surgery and omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. Feb 2001;192(2):172-9; discussion 179-81. [Medline].

Spechler SJ. Epidemiology and natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 1992;51 suppl 1:24-9. [Medline].

Anvari M, Allen C, Marshall J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease: One-year follow-up. Surg Innov. Dec 2006;13(4):238-49. [Medline].

[Best Evidence] Grant AM, Wileman SM, Ramsay CR, et al. Minimal access surgery compared with medical management for chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: UK collaborative randomised trial. BMJ. Dec 15 2008;337:a2664. [Medline]. [Full Text].

El-Serag HB. Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Jan 2007;5(1):17-26. [Medline].

Anvari M, Allen C. Five-year comprehensive outcomes evaluation in 181 patients after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Am Coll Surg. Jan 2003;196(1):51-7; discussion 57-8; author reply 58-9. [Medline].

Armstrong D, Kazim F, Gervais M, Pyzyk M. Early relief of upper gastrointestinal dyspeptic symptoms: a survey of empirical therapy with pantoprazole in Canadian clinical practice. Can J Gastroenterol. Jul 2002;16(7):439-50. [Medline].

Bianchi Porro G, Pace F, Peracchia A, et al. Short-term treatment of refractory reflux esophagitis with different doses of omeprazole or ranitidine. J Clin Gastroenterol. Oct 1992;15(3):192-8. [Medline].

Bowers SP, Mattar SG, Smith CD, Waring JP, Hunter JG. Clinical and histologic follow-up after antireflux surgery for Barrett's esophagus. J Gastrointest Surg. Jul-Aug 2002;6(4):532-8; discussion 539. [Medline].

Bremner RM, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Gastroesophageal reflux: the use of pH monitoring. Curr Probl Surg. Jun 1995;32(6):429-558. [Medline].

Broussard CN, Richter JE. Treating gastro-oesophageal reflux disease during pregnancy and lactation: what are the safest therapy options?. Drug Saf. Oct 1998;19(4):325-37. [Medline].

Bytzer P, Havelund T, Hansen JM. Interobserver variation in the endoscopic diagnosis of reflux esophagitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. Feb 1993;28(2):119-25. [Medline].

Campos GM, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Multivariate analysis of factors predicting outcome after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg. May-Jun 1999;3(3):292-300. [Medline].

Costantini M, Crookes PF, Bremner RM, et al. Value of physiologic assessment of foregut symptoms in a surgical practice. Surgery. Oct 1993;114(4):780-6; discussion 786-7. [Medline].

Dallemagne B, Weerts J, Markiewicz S, et al. Clinical results of laparoscopic fundoplication at ten years after surgery. Surg Endosc. Jan 2006;20(1):159-65. [Medline].

El-Serag HB, Tran T, Richardson P, Ergun G. Anthropometric correlates of intragastric pressure. Scand J Gastroenterol. Aug 2006;41(8):887-91. [Medline].

Fernando HC, Schauer PR, Rosenblatt M, et al. Quality of life after antireflux surgery compared with nonoperative management for severe gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg. Jan 2002;194(1):23-7. [Medline].

Fuchs KH, DeMeester TR, Albertucci M. Specificity and sensitivity of objective diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surgery. Oct 1987;102(4):575-80. [Medline].

Harding SM, Richter JE, Guzzo MR, et al. Asthma and gastroesophageal reflux: acid suppressive therapy improves asthma outcome. Am J Med. Apr 1996;100(4):395-405. [Medline].

Hetzel DJ, Dent J, Reed WD, et al. Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology. Oct 1988;95(4):903-12. [Medline].

Hinder RA, Stein HJ, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Relationship of a satisfactory outcome to normalization of delayed gastric emptying after Nissen fundoplication. Ann Surg. Oct 1989;210(4):458-64; discussion 464-5. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Hunter JG, Trus TL, Branum GD, Waring JP, Wood WC. A physiologic approach to laparoscopic fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Surg. Jun 1996;223(6):673-85; discussion 685-7. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Kauer WK, Peters JH, DeMeester TR, et al. Mixed reflux of gastric and duodenal juices is more harmful to the esophagus than gastric juice alone. The need for surgical therapy re-emphasized. Ann Surg. Oct 1995;222(4):525-31; discussion 531-3. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Koelz HR, Birchler R, Bretholz A, et al. Healing and relapse of reflux esophagitis during treatment with ranitidine. Gastroenterology. Nov 1986;91(5):1198-205. [Medline].

Locke GR 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd. Risk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. Jun 1999;106(6):642-9. [Medline].

McCallum RW, Berkowitz DM, Lerner E. Gastric emptying in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Gastroenterology. Feb 1981;80(2):285-91. [Medline].

Monnier P, Ollyo JP, Fontolliet C, Savary M. Epidemiology and natural history of reflux esophagitis. Semin Laparosc Surg. 1995;2:2-9.

Oelschlager BK, Barreca M, Chang L, Oleynikov D, Pellegrini CA. Clinical and pathologic response of Barrett's esophagus to laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Ann Surg. Oct 2003;238(4):458-64; discussion 464-6. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Ollyo JB, Lang F, Fontolliet CH. Savary-Miller's new endoscopic grading of reflux-esophagitis: a simple, reproducible, logical, complete, and useful classification. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:A100.

Patti MG, Arcerito M, Feo CV, et al. An analysis of operations for gastroesophageal reflux disease: identifying the important technical elements. Arch Surg. Jun 1998;133(6):600-6; discussion 606-7. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Patti MG, Arcerito M, Feo CV, et al. Barrett's esophagus: a surgical disease. J Gastrointest Surg. Jul-Aug 1999;3(4):397-403; discussion 403-4. [Medline].

Patti MG, Feo CV, De Pinto M, et al. Results of laparoscopic antireflux surgery for dysphagia and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Surg. Dec 1998;176(6):564-8. [Medline].

Patti MG, Robinson T, Galvani C, et al. Total fundoplication is superior to partial fundoplication even when esophageal peristalsis is weak. J Am Coll Surg. Jun 2004;198(6):863-9; discussion 869-70. [Medline].

Peghini PL, Katz PO, Castell DO. Ranitidine controls nocturnal gastric acid breakthrough on omeprazole: a controlled study in normal subjects. Gastroenterology. Dec 1998;115(6):1335-9. [Medline].

Pessaux P, Arnaud JP, Delattre JF, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery: five-year results and beyond in 1340 patients. Arch Surg. Oct 2005;140(10):946-51. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Peters JH, DeMeester TR, Crookes P, et al. The treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: prospective evaluation of 100 patients with "typical" symptoms. Ann Surg. Jul 1998;228(1):40-50. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Richter JE. Extraesophageal presentations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Semin Gastrointest Dis. Apr 1997;8(2):75-89. [Medline].

Schillinger W, Teucher N, Sossalla S, et al. Negative inotropy of the gastric proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole in myocardium from humans and rabbits: evaluation of mechanisms. Circulation. Jul 3 2007;116(1):57-66. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Spechler SJ. The columnar-lined esophagus. History, terminology, and clinical issues. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. Sep 1997;26(3):455-66. [Medline].

Spechler SJ, Lee E, Ahnen D, et al. Long-term outcome of medical and surgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux disease: follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. May 9 2001;285(18):2331-8. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Streitz JM Jr, Andrews CW Jr, Ellis FH Jr. Endoscopic surveillance of Barrett's esophagus. Does it help?. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. Mar 1993;105(3):383-7; discussion 387-8. [Medline].

Streitz JM Jr, Williamson WA, Ellis FH Jr. Current concepts concerning the nature and treatment of Barrett's esophagus and its complications. Ann Thorac Surg. Sep 1992;54(3):586-91. [Medline].

Vigneri S, Termini R, Leandro G, et al. A comparison of five maintenance therapies for reflux esophagitis. N Engl J Med. Oct 26 1995;333(17):1106-10. [Medline]. [Full Text].

Zaninotto G, Portale G, Costantini M, et al. Long-term results (6-10 years) of laparoscopic fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg. Sep 2007;11(9):1138-45. [Medline].

[Best Evidence] Hemmink GJ, Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, et al. Esophageal pH-impedance monitoring in patients with therapy-resistant reflux symptoms: 'on' or 'off' proton pump inhibitor?. Am J Gastroenterol. Oct 2008;103(10):2446-53. [Medline].

[Best Evidence] Horvath A, Dziechciarz P, Szajewska H. The effect of thickened-feed interventions on gastroesophageal reflux in infants: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Pediatrics. Dec 2008;122(6):e1268-77. [Medline]. [Full Text]