International Journal of Clinical Practice

A Systematic Literature Review

Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66(11):1056-1078. © 2012 Blackwell Publishing

Abstract and Introduction

Abstract

Background and Aims: The use of herbs and dietary supplements (HDS) alone or concomitantly with medications can potentially increase the risk of adverse events experienced by the patients. This review aims to evaluate the documented HDS-drug interactions and contraindications.

Methods: A structured literature review was conducted on PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, tertiary literature and Internet.

Results: While 85 primary literatures, six books and two web sites were reviewed for a total of 1,491 unique pairs of HDS-drug interactions, 213 HDS entities and 509 medications were involved. HDS products containing St. John's Wort, magnesium, calcium, iron, ginkgo had the greatest number of documented interactions with medications. Warfarin, insulin, aspirin, digoxin, and ticlopidine had the greatest number of reported interactions with HDS. Medications affecting the central nervous system or cardiovascular system had more documented interactions with HDS. Of the 882 HDS-drug interactions being described its mechanism and severity, 42.3% were due to altered pharmacokinetics and 240 were described as major interactions. Of the 152 identified HDS contraindications, the most frequent involved gastrointestinal (16.4%), neurological (14.5%), and renal/genitourinary diseases (12.5%). Flaxseed, echinacea, andyohimbe had the largest number of documented contraindications.

Conclusions: Although HDS-drug interactions and contraindications primarily concerned a relatively small subset of commonly used medications and HDS entities, this review provides the summary to identify patients, HDS products, and medications that are more susceptible to HDS-drug interactions and contraindications. The findings would facilitate the health-care professionals to communicate these documented interactions and contraindications to their patients and/or caregivers thereby preventing serious adverse events and improving desired therapeutic outcomes.

Methods: A structured literature review was conducted on PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, tertiary literature and Internet.

Results: While 85 primary literatures, six books and two web sites were reviewed for a total of 1,491 unique pairs of HDS-drug interactions, 213 HDS entities and 509 medications were involved. HDS products containing St. John's Wort, magnesium, calcium, iron, ginkgo had the greatest number of documented interactions with medications. Warfarin, insulin, aspirin, digoxin, and ticlopidine had the greatest number of reported interactions with HDS. Medications affecting the central nervous system or cardiovascular system had more documented interactions with HDS. Of the 882 HDS-drug interactions being described its mechanism and severity, 42.3% were due to altered pharmacokinetics and 240 were described as major interactions. Of the 152 identified HDS contraindications, the most frequent involved gastrointestinal (16.4%), neurological (14.5%), and renal/genitourinary diseases (12.5%). Flaxseed, echinacea, andyohimbe had the largest number of documented contraindications.

Conclusions: Although HDS-drug interactions and contraindications primarily concerned a relatively small subset of commonly used medications and HDS entities, this review provides the summary to identify patients, HDS products, and medications that are more susceptible to HDS-drug interactions and contraindications. The findings would facilitate the health-care professionals to communicate these documented interactions and contraindications to their patients and/or caregivers thereby preventing serious adverse events and improving desired therapeutic outcomes.

Introduction

The marketing and consumer use of herbs and dietary supplements (HDS) has risen dramatically in the USA over the past two decades. [1,2] It is estimated that > 50% of patients with chronic diseases or cancers ever use HDS, [3] and nearly one-fifth of patients take HDS products concomitantly with prescription medications. [4,5] Despite their widespread use, the potential risks associated with combining HDS with other medications are poorly understood by these consumers. Although many HDS users believe that HDS are safe, [6] HDS products have been reported to be associated with mild-to-severe adverse effects such as heart problems, chest pain, abdominal pain and headache. [2,7,8]Because a majority of patients often fail to disclose that they have taken HDS products to their healthcare providers, e.g. one study estimated only 30% disclosure, [9] patient-provider communication concerning the risks and benefits of HDS is critically important.

A major challenge for healthcare providers in counselling patients about HDS is that the available clinical evidence may be ambiguous and sometimes conflicting for HDS adverse events and drug interactions. [10,11] Also, there are often practice-based barriers to identifying the evidence on HDS–drug interactions, [12] including lack of familiarity or access to HDS-related textbooks and databases.[13,14] In general, fewer and less rigorous studies are available for HDS than that of prescription drugs, particularly with respect to randomised controlled clinical trials. [15] Many available references for HDS list numerous 'potential HDS–drug interactions' with little clinical significance or risk. Many reference books are replete with errors that serve only to confuse healthcare practitioners or consumers. The aim of this review was to provide healthcare professionals with a resource that concisely summarises the scientific evidence for HDS–drug interactions and contraindications from 2000 to 2010.

Methods

Evidence Resources and Literature Search

This review of HDS–drug interactions and contraindications focused on the evidence in the primary literature and tertiary literature (i.e. textbooks) related to HDS or drug interactions.[16–21] Important online resources about HDS, including the website of National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), [22] and Office of Dietary Supplements [23]were also included. The definition of HDS used for this study was the official definition of dietary supplements as stated in the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA). [24] HDS refers to any herbal product or dietary supplement product containing one of the following ingredients: vitamin, mineral, other botanical, amino acid, or other dietary substance. Thus, traditional foods or fruit products, not listed in the definition (e.g. avocado, grapefruit, and onion, etc.), were not included in this review.

The primary literature was obtained by searching databases, i.e. MEDLINE (via PubMed), EMBASE and Cochrane Library. Search terms included, but were not limited to the medical subject headings (MeSH terms) or key words that encompassed 'herb drug interactions', 'dietary supplements' OR 'vitamins' OR 'minerals' OR 'amino acids' OR 'botanical' OR 'herbal medicine' OR 'phytotherapy' combined with 'contraindications' OR 'drug interactions'. The searches were performed in English only for the period of January 2000 to December 2010. The articles were selected based on the titles and abstracts and reviewed independently by two authors (HHT, HWL). Literature without related information, including studies regarding efficacy of HDS, regulation of HDS or methods of assay, was excluded. All relevant articles were selected without restriction for animal studies, clinical trials, observational studies (including case reports) or review articles.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Two standardised data abstraction checklists were developed and used to perform the review (one for the HDS–medication interactions and the other for HDS contraindications). All pairs of HDS–drug interactions documented in the retrieved literature sources (except for those interaction pairs with consequences that may benefit to users) were extracted. Because most HDS products or ingredients are not recommended for use during pregnancy or lactation, [25] documented contraindications for these conditions were not further reviewed. All relevant data were extracted, compiled and classified all by one qualified reviewer, and then validated by another. Any disagreements related to the abstraction of data were resolved by consensus.

We grouped HDS products/ingredients into three categories: herb/botanical, vitamin/mineral/amino acid (VMA) and others. The most common drugs were grouped according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. [26] Possible mechanisms and the severity ratings of each pair of interactions were retrieved using the Interactions database in MicroMedex® [27] and 'Natural Product/Drug Interaction Checker' in Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database® (NMCD®). [28] We categorised the mechanisms for pairs of interactions into four types: pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, both (pharmacokinetics plus pharmacodynamics) and unknown. The severity of each documented interaction was categorised as contraindicated, major, moderate and minor based upon MicroMedex®, and major, moderate and minor based upon NMCD®, respectively. The definitions of 'major', 'moderate' and 'minor' were similar in these two databases. For instance, a major interaction may cause life-threatening damage and/or serious adverse effect(s), and a minor interaction would result in a negligible effect(s). However, contraindicated interactions were rated as 'major' severity in NMCD®. The types of contraindications were categorised based on Goldman: Cecil Medicine®. [29] All data were compiled and managed using an Excel spreadsheet. Descriptive analyses to define the frequency or proportion of the evidence associated with the interaction pairs, the corresponding mechanisms and severity ratings of interactions and the types of contraindications for certain populations or patients was performed.

Results

Literature Search

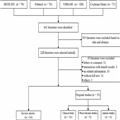

Finally, 461 articles of primary literature were initially identified. Eighty-five articles with full text, including 54 review articles, other than the 6 books and 2 web sites were selected for further review (Figure 1). The summaries of the animal studies, observational studies and clinical trials to retrieve information about HDS–drug interactions and contraindications for the original studies are listed in Table 1 , Table 2 and Table 3 , respectively. The summaries of the retrieved books and reviewed articles to retrieve information about HDS–drug interactions and contraindications were listed in Appendix 1 ,Appendix 2 and Appendix 3 , respectively. Among the original studies ( n = 31), more than half ( n = 16) were clinical trials. All of these articles contained information about HDS–drug interactions, [12,30–113] but only five articles provided descriptive information about HDS contraindications. [55–57,59,102]

Quantity of Retrieved Evidence

After excluding the evidence regarding HDS not recommended for human use (i.e. anvirzel, belladonna, chaparral, comfrey, ephedra and pennyroyal) [16,19,21–23] and the duplicates, a total of 1491 unique pairs of documented interactions between HDS and individual drugs were identified. Among these pairs, 814 pairs (54.6%) were retrieved from the primary literature, 1018 pairs (68.3%) from books and only 23 pairs of interactions were identified in the two reviewed web sites. Among these interactions, the corresponding mechanism and severity was determined for 507 pairs (34.0%) using MicroMedex® and 763 pairs (51.2%) in the NMCD® online database. In total, 882 pairs (59.2%) of documented HDS–drug interactions were identified for their potential mechanism and severity. In terms of contraindications, there were 128, 15 and 9 documented HDS contraindications retrieved from books, primary articles and web sites, respectively, for a total of 152.

HDS–drug Interactions

Among all included interactions between HDS and individual drugs, 166 different herbs/botanical products, 28 VMA and 19 other supplements accounted for 890 pairs (59.7%), 529 pairs (35.5%) and 72 pairs (4.8%) of documented interactions, respectively (Figure 2). The top five herbs/botanical products, which were documented to have the most interactions with individual medications, were St John's Wort ( Hypericum perforatum), ginkgo ( Ginkgo biloba), kava ( Piper methysticum), digitalis (Digitalis purpurea) and willow ( Salix alba). For example, St John's Wort, magnesium, calcium, iron and ginkgo have been documented to interact with 147, 102, 75, 71 and 51 individual medications, respectively. Furthermore, a total of 509 unique drugs contributed to the 1491 documented pairs of interactions with HDS. The majority of these medications ( n = 100) were categorised as treatment for central nervous system (CNS), second were those medications affecting the cardiovascular system and then systemic anti-infective drugs ( n = 90 and 75, respectively) (Figure 3). The medications that most contributed to documented interactions with HDS were warfarin, insulin, aspirin, digoxin and ticlopidine. Not surprisingly, warfarin was documented to have interactions with over 100 HDS entities (Figure 4).

Among 882 pairs of interactions with identified mechanisms, a total of 373 pairs (42.3%) were attributable to pharmacokinetic-related mechanisms, i.e. affected the absorption, distribution, metabolism or excretion of the HDS/drug. Approximately 40.1% of all interaction pairs accounted for pharmacodynamic-related mechanisms, and 8.5% were attributed to a combination of both mechanisms. No mechanism was identifiable for the remaining 9.1% of pairs. Among the 373 documented HDS interaction pairs that were pharmacokinetic-related, 87 pairs were associated with St John's Wort (23.3%), whereas calcium supplements were involved in 47 pairs of documented interactions (12.6%), and iron was involved in 42 pairs of interactions (11.3%). St John's Wort was documented to reduce the effectiveness of alprazolam, amitriptyline, imatinib, midazolam, nifedipine and verapamil via the CYP (Cytochrome P450) 3A4 pathway, and the plasma levels of fexofenadine and digoxin via PgP (p-glycoprotein) pathway. Some drugs (i.e. atorvastatin, cyclosporin, indinavir, nevirapine and simvastatin) were documented to interact with St John's Wort through both pathways. [37,99] Among the 354 documented interactions that were pharmacodynamic-related, kava accounted for 4.8% pairs of interactions (17 pairs). St John's Wort and ginkgo were both involved in 15 pairs of interactions (4.2%). Risk of additive serotonergic effects were increased when St John's Wort was used concurrently with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), or tryptamine-based drugs causing symptoms of anxiety, dizziness, restlessness, nausea and vomiting. [16–18,20] As a result of their pharmacological actions on the GABA receptor, synergism in CNS adverse events may result from taking barbiturates or benzodiazepines in combination with kava. [16,20,98] Furthermore, kava may worsen the extrapyramidal effects associated with the use of droperidol, haloperidol, metoclopramide or risperidone because of a dopamine. [21,98]

Among the 507 documented interaction pairs identified with a severity rating in MicroMedex®, 69.4% were categorised as the moderate interactions, 17.2% as major interactions, 10.3% as minor interactions and 3.1% were attributable to the contraindications. As for the 763 pairs of documented interactions being identified with the severity rating based on the NMCD®, the majority documented interaction pairs were categorised as moderate (69.2%), major (26.5%) and minor (4.3%). Approximately, 240 documented HDS–drug interactions were categorised as major severity in either database ( Table 4 and Table 5). For example, the following pairs of interactions were considered as being contraindicated for concurrent use in MicroMedex®: l-Tryptophan vs. MAOI (i.e. isocarboxazid, phenelzine and tranylcypromine) or venlafaxine and St John's wort vs. protease inhibitors (i.e. amprenavir, fosamprenavir and indinavir), irinotecan, rasagiline or voriconazole, respectively. Among the 390 documented interaction pairs having severity ratings in both databases, 41.3% were inconsistent. For example, the combination of alfalfa ( Medicago sativa) and warfarin were considered as the minor interaction in MicroMedex®; however, it was rated as the major interaction in NMCD®. The combination of St John's Wort with quetiapine, quinidine, risperidone or sildenafil gave severity ratings major according to NMCD®, and no interaction was reported in MicroMedex®.

HDS Contraindications

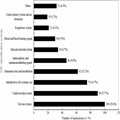

Fifty-nine HDS from 152 reports were contraindicated for use among patients with specific disease states. The reports were classified into 19 disease states, including gastrointestinal diseases, neurologic disorders, renal/genitourinary diseases, neoplastic disorders, diseases of the liver/gallbladder/bile ducts and cardiovascular diseases (Figure 5). Flaxseed ( Linum usitatissimum), echinacea ( Echinacea purpurea) and yohimbe ( Pausinystalia yohimbe) had the highest number of documented contraindications. For example, flaxseed was documented to have contraindications associated with gastrointestinal disorders such as acute or chronic diarrhoea, oesophageal stricture, inflammatory bowel disease, hypertriglyceridemia and prostate cancer. [21] Echinacea was contraindicated for use among patients with rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, leukosis, multiple sclerosis, tuberculosis and HIV infection. [16,18] Yohimbe was contraindicated in patients with anxiety, bipolar disorder, depression, mania and schizophrenia, as well as benign prostate hypertrophy and kidney disease. [21,22]